A Thousand Tiny Acts

Betting the Farm on the Physical World in the Age of AI

the threshold

I’ll never forget my grandpa’s shed office, perched atop a hill at the end of a long driveway on the edge of the Texas Hill Country. When you stepped across that threshold, you entered another world. The lights were just right. Soft classical music played. The room smelled faintly of homemade soap and herbs from my grandma’s workspace in the corner. Everything in there had a place — and a name. Papa loved naming his things. The intercom, the paperweight, the lawnmower. To him, how a bin of books looked on the highest shelf of the closet mattered just as much as how the front entrance to the farm did.

The room didn’t just look right — it felt right, as if his care had soaked into the walls over time.

That care was why some of the wealthiest clients in the region — even a U.S. President — would wait years for him to build their homes. And yet he and my grandma lived for years in an old travel trailer while they slowly saved to build their own. That trailer couldn’t have been worth more than few thousand dollars, but it was the cleanest, most inviting space imaginable. Every time you ducked to fit through the aluminum door, you were greeted by soft lamps, gentle music, and Grandma Jacque’s joyful smile. It didn’t feel poor. It felt deeply loved.

The trailer — nestled carefully at the edge of the trees, with a small wood porch Papa had framed to protect the doorway from rain and sun — was the humble hardware. Grandma Jacque’s cheery, graceful presence was the software. Together, they made a beautiful little world.

I didn’t know it then, but that little farm set the course for my future. It taught me that beauty isn’t about money or luxury. It’s about love — a thousand tiny, mundane acts of delightful care. You might not notice any one of them, but you immediately feel the result.

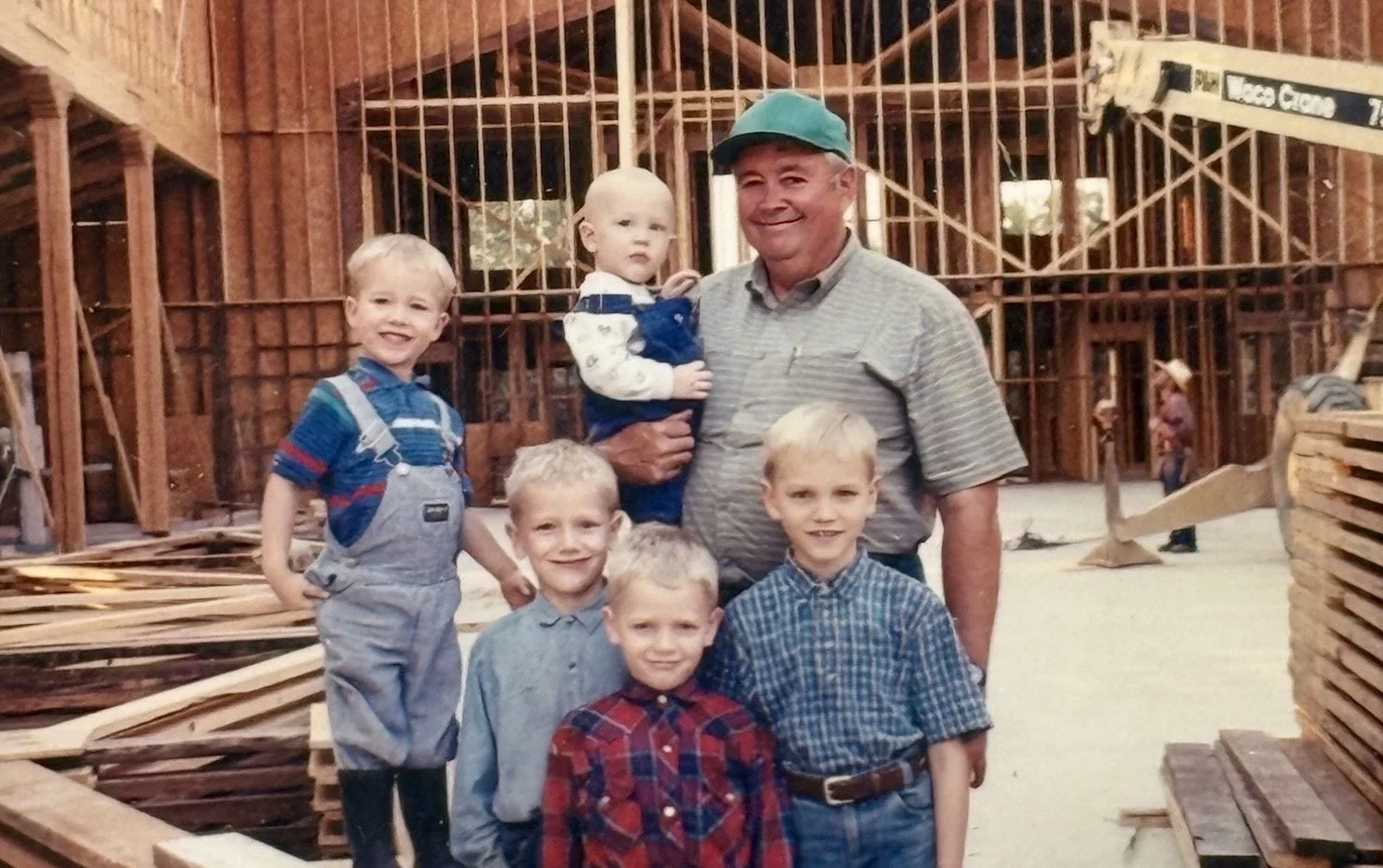

Starting our apprenticeship young with Papa Byron

the thesis

Environments are powerful. Long before we act, create, or decide anything, we are being formed by the places we inhabit.

Over the last two centuries, we’ve become remarkably good at producing things cheaply and efficiently. Tools, systems, goods, services, information—and now even creativity itself — are abundant and increasingly automated. And yet in the process, this machine has all but devoured something essential: places that nurture belonging, wholeness, and beauty. Places that form humans well.

Place has two inseparable components: the physical environment that shelters us, and the community that gives it life — hardware and software. You can’t have one without the other. A beautiful building without love is a hollow shell. But when both come together — the structure and the spirit — beauty happens. A location becomes a place, sometimes even a world.

The digital age makes physical beauty more important, not less. You can’t download an environment — at least not a good one.

I’ve come to believe our deepest need is not faster tools or more convenience, but better inputs: places and practices that form us slowly. AI will build a lot of dazzling things, but it won’t ever build worlds of real belonging or beauty.

Many of us feel placeless. As if we’ve been exiled. But we rarely stop to ask — from where?

garden → tower → machine

The story of humans begins in a garden. Before long, we left to begin building cities, tools, and eventually a tower—each meant to free us from dependence on the land and on one another.

The Tower of Babel is less a story about ambition than fragmentation: a people attempting to secure unity and meaning through their own design end up unable to understand one another, divided and scattered.

And the story repeats. Consider the strange loneliness of social media — millions of people each desperate for real connection, speaking the same language, but somehow less able to understand one another than ever. The tower keeps getting built. And it keeps falling.

The industrial age promised liberation through productivity. The digital age promised connection through abstraction. Now artificial intelligence promises relief from labor itself. Each era delivers genuine breakthroughs. And each, as a byproduct, leaves us more dislocated from place, from one another, and from meaning.

back to eden, via art

When God created humans and put them in the perfect environment, He also gave them a task: to tend, protect, and cultivate it. The ultimate Artist saved some of the art to be ours, in harmony with His. That work is not burdensome. It is joyful, because art is the product of love.

“It is the artist who recognizes the supreme force above him and works gladly away as a small apprentice under God’s heaven.” —Solzhenitsyn

Two years ago, I experienced an echo of what we’ve lost — and what’s possible—while visiting Babylonstoren, a restored 17th-century farm and village in South Africa.

Wandering its gardens, I was taken by the care woven into even the smallest details: long paths leading to quiet gazebos, water moving gently through stone channels, fruit-laden citrus trees perfuming the air. Life was everywhere — butterflies drifting, ducks quacking, bees humming.

A small corner of the garden at Babylonstoren

The place radiated the love poured into it. And so did its people. I was moved by the warmth of each person we encountered, from cooks to weed pullers. It became clear that the gardens hadn’t just been shaped by the people—the people had been shaped by the gardens they tended. I spent hours there doing nothing but being — belonging — becoming.

Harvest time at Babylonstoren

Beyond the gardens stretched rolling hills covered in vineyards, and beyond those hills rose rugged mountain peaks. The careful work of human hands meeting the majesty of something greater. Stewardship and nature, earth and heaven, in quiet harmony.

Nature is more than the canvas. It is the masterpiece. And we are each invited to make small, complementary works within it.

the inputs crisis

We live in an environment flooded with information posing as truth, stimulation without beauty, and connectivity without wholeness. This is not neutral — humans are porous. We are formed by what we repeatedly take in.

Classical thinkers from Aristotle to Aquinas understood this clearly. We become what we attend to. Environments shape habits, and habits shape character. The places we live, work, and socialize are constantly making us into certain kinds of people, whether we notice or not.

The mistake of modernity was thinking abstraction would free us from place. Instead, it made place all the more precious. This is why people are drawn — often without words — to analog tools, slow routines, hand-built things, and places with visible age and imperfection. We want what was created and valued by other humans, not machines. We are hard-wired for human connection, both with humans directly and with what they create. Yes, we know the difference—even in the age of AI.

And we always will.

the highest-order input

Nature is the highest-order input because it is the only environment not designed by human will. It precedes us, and that matters. Nature is the home we were made for, the place we feel most alive.

And yet we have largely built sprawling cities that treat nature as an afterthought, begrudgingly swept to the edges or used for some marginal economic benefit or “ROI.” The world where humans actually live has a lot more steel, asphalt, and concrete, and far fewer trees, grasses, and rocks than it once did. We should not be surprised that such places shape us in return.

What we do to our local places, we do to the larger world. The health of the whole begins with the care of the smallest part.

A beautiful place trains the soul the way good music trains the ear. Light, quiet, proportion, plants, organic materials, land: these are not neutral backdrops. They are formative forces. A quiet space calms and heals the nervous system. A well-proportioned, well-lit room restores clarity. A garden can soften even the hardest heart.

In an age when outputs multiply endlessly and meaning feels scarce, where a million artificial distractions compete for our attention all at once, the hunger for real environments — for truth we can touch and feel — will only grow.

People will not starve for things to do. They will starve for places to be, to belong, to become.

Our backyard and studio/guesthouse - The Nook

cities & boundaries

I do not mean to categorically condemn cities. Cities can be humane and beautiful, or brutal and deforming. The good ones make room for nature as their heartbeat. They grow slowly, with care, and they know their limits. The bad ones chase scale and efficiency at devastating cost, fracturing life and belonging for the sake of production.

Even there, we have an opportunity: to create contrast. To build beauty one corner at a time. Small pockets—neighborhoods, courtyards, communities—where belonging can take root.

Wherever we build, boundaries matter. Not barriers to keep the unwanted out, but thresholds that protect attention, nurture belonging, and make room for love. When you cross into a good room, home, garden, church, village, city — or even a shed — something settles. You feel it immediately. There is coherence. And peace.

Scripture captures this beautifully: love as a garden enclosed, with fruitful branches reaching over the wall. A protected place of beauty does not hoard its goodness. It overflows it.

community as software

Beautiful places alone are insufficient. I’ve said that place has two inseparable components—the hardware and software. Now let me dwell on the second.

Architecture and land are the hardware, but community—shared life, love, stewardship and belonging—is the software. A beautiful building without love is just a hollow shell, an empty pitcher for the thirsting soul. But when care, warmth, camaraderie, and hospitality come together in a good physical space, something happens. A place comes alive and begins to breathe. And so do its people.

We do not heal fragmentation through private optimization or algorithmically-curated feeds. We heal it through shared life in shared places, practiced patiently over time. People shape places, and places shape people, in a continual, reinforcing exchange.

Last year, in the Driftless Region of Wisconsin, I saw another glimpse of this.

A small group of families — an unlikely blend of Amish and Southern California backgrounds — have left their old lives behind to live out agrarian community. They live on private homesteads, run local businesses, and share an off-grid farm and garden. At different intervals depending on the season, the community comes together to worship, celebrate, and work in the garden — an organic mirror of the beautifully diverse folks themselves. The place forms the people, the people form the place.

This community isn’t perfect. None are. But it embodies the marriage of place and people — hardware and software — in a hopeful harmony. And it is part of a larger experiment—one I find myself a child of, quite literally.

Attending a friend’s wedding at the Wisconsin farm last October

the place that shaped me

I grew up in an intentional agrarian Christian community.

In the early 1970s, a young couple moved from Texas to the slums of lower-east Manhattan to serve the broken and displaced. Within a few years, the group—now including many young families who’d experienced spiritual transformation and real hope — felt the call to root itself in an agrarian setting: a place to raise children, grow food, and work with their hands. They ended up in Colorado, where both my parents stumbled across them as searching youth, and eventually settled on a farm in Central Texas, where I was born and spent the first twelve years of my life.

Checking fruit tree blossoms with our dad

My industrious (and brave) parents homeschooled all ten of us kids on our small homestead. We built everything we could dream up — miniature backyard villages, barns for our animals, ponds to catch rainfall, root cellars to keep our food, and a maze of trails to explore. And we knew and loved our neighbors. My grandma Jan lived closest, her small cottage right across the road from ours. She nurtured a love for fine art in us, pouring hours a week into art lessons that taught me to see and appreciate beauty.

My other grandparents lived a few miles down the road (where the office was) on a farm they’d saved for years to afford. When we weren’t busy with school or projects, or riding along to construction sites with our dad, my brothers and I worked alongside my grandpa, clearing brush, herding cows, building fence. Slowly, that briar-infested piece of land turned into a spectacular place. And we turned into young men. My grandpa taught me and my seven brothers to care about our work by his patient, consistent example. So did my parents and a whole community of neighbors who cared about theirs.

That community has now inspired about a dozen others around the world, including the one in Wisconsin. I owe my love of place to that childhood — both the wonderful people and the place that shaped me.

what we’re doing about it

As an adult, I’ve tried to carry that formation forward by designing and building small, human-scale places that hopefully inspire others. “Art in nature,” as I’ve come to fondly call it.

Shadow Bend — one of seven cabins at Live Oak Lake

These include Live Oak Lake, a Japanese- and Nordic-inspired landscape hotel; a five-acre community fruit orchard and garden near my home; and a small studio and guesthouse called The Nook. Together with family, neighbors, and friends in Idaho — where I spent the second half of my childhood after we moved to help plant a new community there — we’ve embarked on a decades-long effort to restore and revitalize our beloved little town of Deary.

Before… (the old Deary Ford garage)

After… (reborn as an artisan bakery & creamery)

Deary is one of thousands of rural towns across America that once buzzed with life but now suffers the slow death of attrition. They say it takes a village — in this case, to restore one. One by one, we’ve restored old brick buildings by hand and opened businesses to serve the community: a creamery, bakery, general store, butcher shop, quilt store, a train depot and rail car turned boutique hotel, tree and flower nursery. These have transformed the local aesthetic and economy, and provide meaningful work. I hope this story will repeat across the country. It already is.

A little corner of Deary, including the old train depot turned boutique hotel

I don’t pretend any of this is easy. None of these are blueprints, just experiments — fragile, imperfect, and still unfolding.

For those serious about community, it’s a lot like growing a garden. It takes perseverance. Willingness to work through messy seasons. People will let you down, you will let them down. You cannot be everywhere or do everything. That’s part of what it means to be rooted. Community is messier than solitude. But it’s also life-giving like nothing else.

The 5-acre fruit orchard my friends & I planted for our community

Building beautiful physical spaces is hard, too. Capital can be hard to come by, projects fail, plants die. Building things beautifully takes extra time, ties you down, and gives you a thousand excuses to cut corners. Then there’s maintenance — the lost art of upkeep—which in some ways is even harder than building.

And here’s the thing: you cannot build the hardware and hire out the software. You cannot design a beautiful place and then leave. Presence is the cost. But it’s also the point. And I truthfully wouldn’t trade my childhood or life today for anyone else’s.

My wife Helen and I live a stone’s throw from where we each grew up. We’re trying to carry forward these same values to our children. This way of life is not for everyone, and that’s not our goal. It’s simply my testimony — a case study of what one model could look like.

We need a diversity of efforts, a patchwork quilt of wholehearted place-making.

what you can do about it

We are all place-makers and place-keepers. And we get to choose what kind of place we will give our children.

In an age of infinite digital outputs, the most needed work is not faster technology and better tools. Those matter, and I’m thankful for many of them. But something upstream, something deeply human matters more: building and tending places people can belong.

If you’re wondering where to begin, start with what you already have.

Plant a tree you love and learn to keep it. Make one room, one table, one corner of the world the most welcoming, delightful space you can. Don’t wait for the acreage, the funding, the perfect moment. The habit of care is the thing. It scales up, but only if practiced small.

Commit to one real friendship over a real table. Not networking. Not audience-building. Community grows from repeated presence and a common purpose, so you better have a purpose big enough to ask something of you, but local enough to keep you fully engaged. Your neighborhood might be the perfect place to start.

We live in a time that pressures us to care about everything and trains us to care deeply about almost nothing. The care I’m describing is local, but it doesn’t stay local. Faithful attention at a small scale is not a denial of the greater good. It is the only way the greater good is ever truly served.

This is the work I’ve chosen, this is my case for place. I’m betting the farm — quite literally — on the physical world in the age of AI.

I hope our future includes homes and gardens, villages and cities, where the divine does not have to be silent. Ordinary places, tended with extraordinary love. Places where, when you step across that threshold, something settles in you—something you can’t quite name but immediately recognize. The sum of a thousand tiny acts of care, made visible. Made whole.

When I think about what I want to leave my children, I keep coming back to that little trailer with the wood porch Papa framed, the soft lamps, Pachelbel playing. Four thousand dollars, maybe. But so much love poured into it that it shaped everything I’ve built since—and God willing, what’s still to come.

The story of humanity began in a garden. Before it ends, may it return to one. One backyard, one doorway, one threshold at a time.